After reading Invisible Women, I happened to come across this article on WebMD about menstrual pain that lists risk factors like this:

"The following circumstances may make a woman more likely to experience menstrual cramps:

She started her first period at an early age (younger than 11 years).

Her menstrual periods are heavy.

She is overweight or obese.

She smokes cigarettes or uses alcohol.

She has never been pregnant."

Although you would expect a page about period pain to refer to the sex of those who experience it, I wondered if male-specific pages (about erectile dysfunction, for example) would do so to the same extent. If they did not, this could be a case of ‘default male’ thinking that Caroline Criado-Perez argues is responsible for the ‘gender data gap’ that causes problems for people (especially women) around the world1. I think the ‘default male’ phenomena is easily demonstrated by the fact that stick figures are considered ‘stick men’ despite barely resembling either men or women. To draw a woman, you add a skirt, some hair and/or eyelashes to this basic humanoid frame. One of the most striking examples from the book is that archaeologists usually find more male than female skeletons (obviously a mistake).

I found that it was too difficult to scrape text from WebMD, as their pages were not formatted consistently. Instead, I looked at the NHS website. Using the rvest package2, I extracted the content of 15 female-specific and 15 male-specific ‘conditions’ (they were classified as conditions on the website - see the table of results below). I didn’t really need to use web-scraping for this, but I wanted some practice.

Frequency of Gendered Nouns

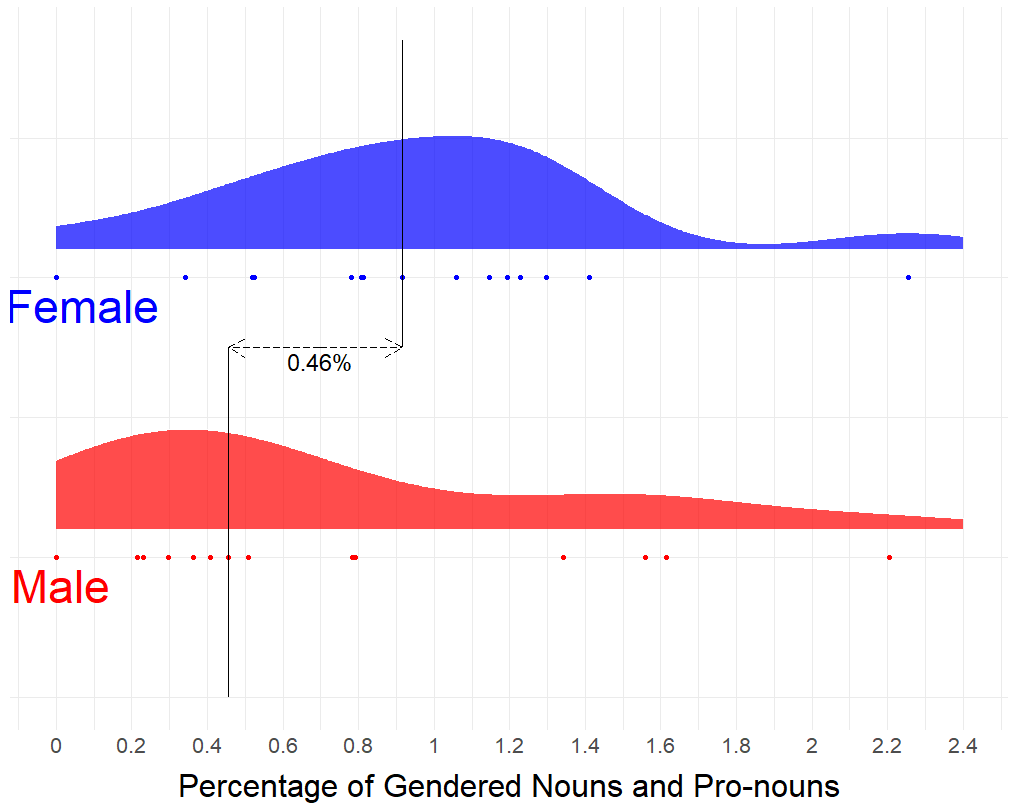

First, I looked at the frequency of gendered nouns and pronouns for all articles specific to each sex. Those nouns being ‘woman’, ‘women’, ‘she’ and ‘her’ for female-specific article, and ‘man’, ‘men’, ‘he’ and ‘his’ for male-specific articles.

Overall, there were 93 female nouns used in the 15 female-specific articles, and 89 male nouns used the male-specific articles. As this does not take into account the length of the articles from which the words came, I do not think this is very useful information.

\(Frequency/Length\) Index

I decided that dividing the frequency of these words by the length of the article would be more informative (as longer articles are bound to have more of any word than shorter ones, making comparison is unfair). These are the results:

The vertical bars represent the median of each group. For female-specific conditions, roughly every 1 in 100 words refers to women. For male-specific conditions, roughly 1 in every 200 words refers to men. Relatively, that is a difference of (roughly) 100%. I don’t know how noticeable this would be, however, as it is only an absolute difference of half a percent (0.46%).

\(Personal/Impersonal\) Ratio

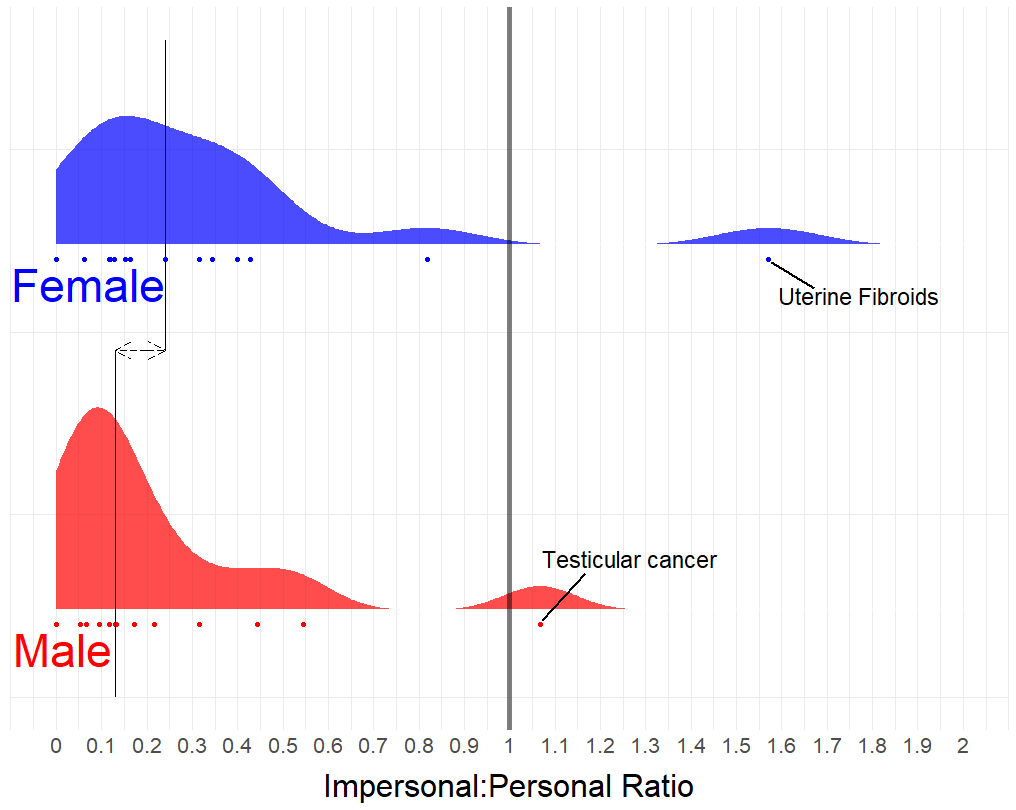

Another way to look at this data is to compare how often each article refers to the reader in the personal sense (by saying ‘you’ or ‘your’) and compare that to how often the sex of the sex-specific article is referred to impersonally (by using gendered nouns). If male-specific pages are more personal than female-specific pages, this could also be interpreted as default-male thinking as ‘you’, a gender neutral term, would be used less often to refer to women.

An impersonal:personal ratio over 1 indicates that the article is more impersonal than it is personal. Only two articles have such a ratio (they are labeled in the figure above). The lower the ratio, the more personal the article is (compared to how impersonal it is). The difference between the median male and female ratios is very small compared to the spread of the data. So I doubt this difference is particularly meaningful.

Conclusion

Based on these data alone, I think the most extreme claim that can be made is that the NHS website more often specifies the sex of a sex-specific article when that sex is female (even when controlling for article length). To make a more general claim like, ‘the way sex-specific conditions are described exhibits male-default thinking’, more sources of condition-descriptions would be needed, as well as greater articulation of the inferential process (by which I mean specifying a hypothesis, explaining how the observations can test that hypothesis and why a test of that hypothesis warrants a conclusion about male-default thinking).

I will might add to this analysis at some point, but for now it is just a useful exercise, not a robust study.

Table of Results

References

- Criado-Perez, C. (2019). Invisible women: Data bias in a world designed for men.

- Hadley Wickham (2019). rvest: Easily Harvest (Scrape) Web Pages. R package version 0.3.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rvest